By Meredith Alexander Kunz, Adobe Research

It began as a lunchtime conversation at the Adobe café in Seattle. The topic was an issue that kept coming up for Adobe customers: It was hard to make their 2D characters come to life with existing tools. How could they animate their artwork more easily?

Two groups—one from Adobe Research, and the other from the Advanced Product Development (APD) group in Adobe’s Digital Video & Audio team—had independently been considering what they could do to help.

At Adobe Research, Wilmot (Wil) Li, a Principal Scientist, and Jovan Popović, an Adobe Fellow, were inventing technologies for transforming static drawings into interactive media. Li had developed methods for converting three-dimensional or two-dimensional artwork into interactive diagrams. Popović collaborated on techniques for animation with physics or human performances (body, face, and hands) and on techniques for doing so quickly on any artwork. Their work, and related advances in machine learning, highlighted the possibility of animating through speaking and acting performance alone.

APD team members were well aware of animation pain points for users. “Folks in the APD group were seeing lots of customers having a tough time trying to use After Effects to rig complicated characters, so we started to formulate a plan to bring character animation to a wider audience,” recalls David Simons, an Adobe Fellow who leads APD. Over lunch, Simons says, “a plan started to come together.”

Popović brainstormed potential directions with Simons and his team. Others soon joined the effort, including Li from Adobe Research and Daniel Wilk and James Acquavella from APD.

They knew they could find a way to make character animation easier for Adobe’s creative customers. What they did not yet know was that this informal exchange would lead to a brand-new product, Adobe Character Animator, and that this product—fast-forwarding to 2020—would be recognized with a technical Emmy Award for its contributions to television.

A New Blueprint

The group began a multi-year project that brought them together into a single team.

Their goal was to create a completely new tool that could seamlessly take 2D art from Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator and turn it into an animated character that could be controlled by a performer being motion-tracked in real time.

“There was no blueprint, so we had to invent one,” says Popović, who moved into APD’s space in the Seattle office’s first floor to work out the original warping engine with collaborators.

“The entire system is innovative, since there were no mainstream products for performance-based 2D animation,” he explains.

When the team began, they were taking a page from previous work in the 3D realm. Li explains that motion capture for 3D animation has been around for years. However, that approach was expensive and driven by specialized equipment. An early full-length film example of this 3D work was in 2002’s The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, where an actor’s motion was captured in a 3D character, Gollum.

By contrast, the Adobe effort sought to democratize a streamlined form of facial motion tracking for 2D artists and animators.

Turning 2D Art into Dynamic Content

Li saw the promise of the project early on. “I was drawn to the idea of transforming static 2D artwork into interactive, dynamic content,” he says. “There’s something magical about taking a flat picture and making it move and respond to a user’s performance.”

But to be able to turn 2D artwork—for example, famous cartoon characters with unrealistic features such as Homer Simpson—into motion-captured animations using an automated system had significant challenges.

The new technology would have to be able to map a character to a user’s performance, including facial expressions, speech, and gestures, and to transfer that to the character “in a way that looks natural and gives artists control over their animation,” Li says.

A Novel Combination

Ultimately, many complex moving parts had to unite to create an overall system that could handle these demands. “Individual technologies were challenging to develop, but getting them all to work together was the hardest thing to get right,” says Popović.

Lip sync technology was perhaps the hardest feature to design, says Simons, but the tool’s success doesn’t ride on one single capability. “It’s more about combining lots of existing technologies into a novel combination.”

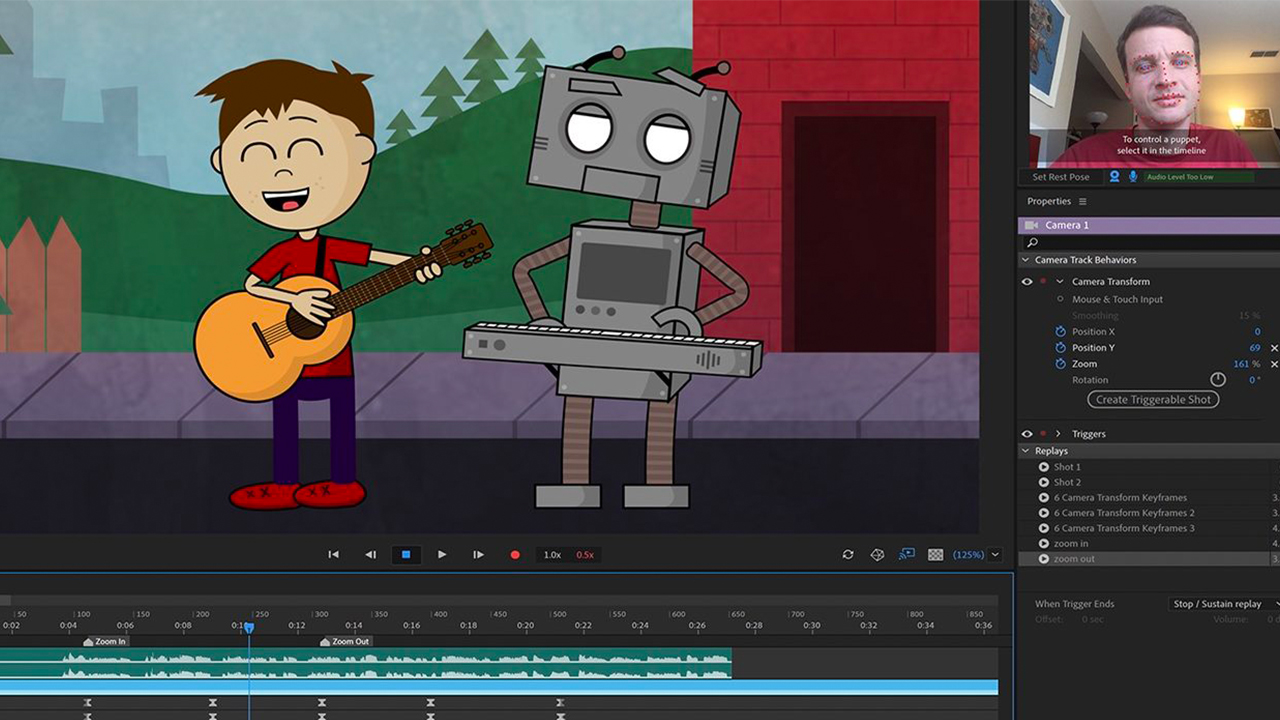

Today, Character Animator uses a camera and microphone to capture the user’s voice, expressions, and head movements. These elements animate a puppet, along with keyboard or controller inputs that can trigger movements, behaviors, and poses.

In a massive work of synthesis, Adobe Research and APD partnered to create a range of features. Here are a few:

- Lip Sync behavior matches the user’s vocal performance into cartoon mouth motion.

- Face behavior converts a user’s facial expressions into cartoon expressions.

- Puppet Warp naturally deforms 2D artwork in response to a user’s motions.

- Dangle behavior enhances animations with expressive, dynamic simulation. It turns 2D motions into automatic secondary animation.

- Characterizer allows users to transform their own image into a stylized animated character or artwork. For example, a user’s face could appear in the style of a Van Gogh painting.

These features can be hand-tuned by users in the tool. You can quickly see your own face and expressions being tracked and mimicked by cartoons. Users can create in real time, or record and edit later. (To give it a whirl, check out the Adobe Character Animator page for info.)

Open, Collegial, Collaborative

The cooperation between the two Adobe groups went beyond an ordinary partnership on a single feature or even a set of features. Members of the group still meet weekly. Says Li: “It has been an incredibly open, collegial, and collaborative experience.”

The software was distributed as a public beta, allowing the team to gather maximum feedback from users, who were eager to give it a try.

Early on, the tool was employed by the team at The Simpsons, who were first to use it in live TV broadcasts. That included an audience “call-in” segment featuring Homer Simpson in May 2016. In November 2016, Simpsons characters appeared live, using Ch, at the Adobe MAX Creativity Conference.

Also in 2016, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert began to do live interviews with fictionalized animated politicians, injecting a current-events flavor that later spun off into Showtime’s Our Cartoon President—an entire TV series that relies on Character Animator. And outside of Hollywood, many more creative users are taking advantage of this software to make their cartoon characters come to life.

And in a fitting capstone, this fall, Adobe Character Animator will be honored as a “pioneering system for live performance-based animation using facial recognition” with a technical Emmy award by the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. The Emmy is “a wonderful testament to what the team accomplished,” says Popović.