By Meredith Alexander Kunz, Adobe Research

Creators making videos—for films, trailers, ads, vlogs, or other forms of storytelling—care about engaging their audiences. But they also are interested in what happens after their videos are viewed. Some critical questions are: Will you remember that video tomorrow, or the day after that? Will it leave a lasting impression?

It turns out that these questions have historically been pretty hard to answer because of our inability to measure memorability. Now, Adobe Research scientists are finding new ways to understand what people remember about videos.

Sumit Shekhar, a research scientist based in Bangalore, discovered that there was very little previous work done on video memorability. Some scientists have used fMRI scans—functional magnetic resonance imaging—to study how people remembered videos. But fMRI brain studies are very expensive, require special equipment, and are not available outside of medical research labs. That kind of measurement was not scalable.

Inspired by a conversation with Adobe Research colleague Atanu R Sinha, Shekhar and collaborators—also including Dhruv Singal and Harvineet Singh—identified a new way to measure what people remember in video.

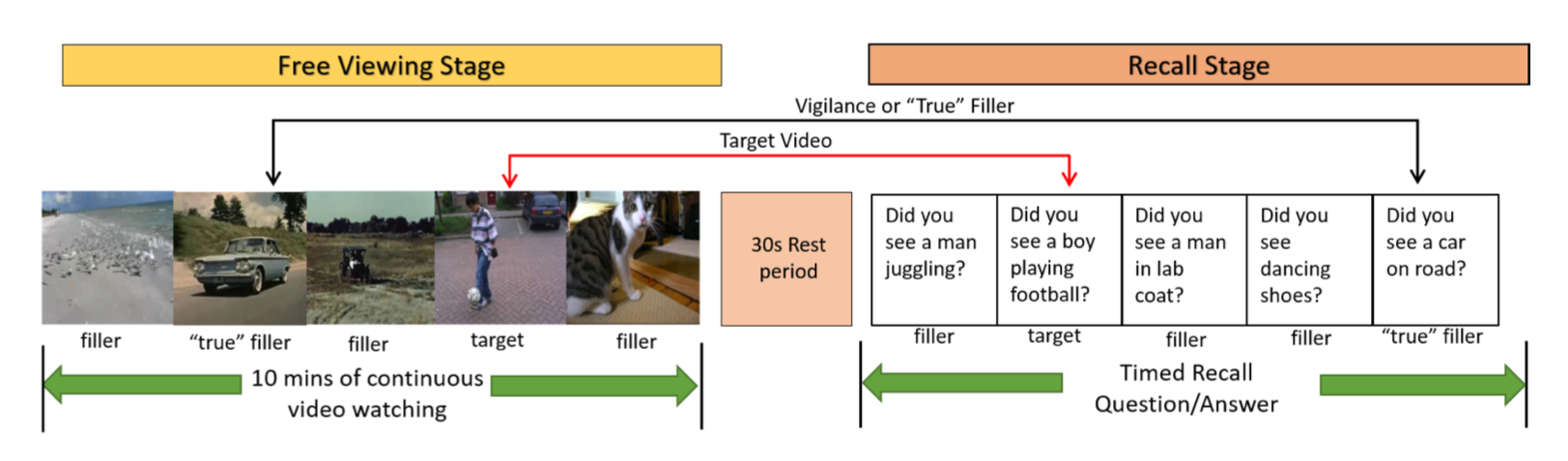

“We designed an experiment where we tried to emulate browsing behavior, when you see a stream of video content on social media,” explains Shekhar. “We first showed a series of videos to the user, without sound. The user was given 10 minutes to view 40-second clips.” Some clips were “filler” content—not the target of the memory study— but included to add more imagery to the mix, helping to control for bias.

Researchers then asked the participants questions such as, “Did you see a man juggling, a car turning, or, a boy playing football?” They measured the time taken to answer each question, hypothesizing that the length of reaction time indicated how memorable the content was. If the recall was fast, the scene was deemed more memorable.

Shekhar and team’s key findings? “Nature videos are less memorable than humans and animals,” he says.

“Cats were top—cats were more memorable than a waterfall,” he adds. (So there really is a reason why cat videos dominate the Net.) Human faces were also a big draw. These kinds of results are similar to memorability findings for static images, Shekhar reports.

The team also found that video-specific factors played a role. When a video has motion and dynamics, such as zooming in and out, it is more memorable, for example.

The researchers followed their initial study with an experiment on the relationship of video memorability to how a “video summary”—a shortened version—performs. As you might expect, parts of the video that are more memorable can be used to make a shortened video with a higher degree of impact.

Shekhar points out that memorability is a more sophisticated measurement than a previously used metric for videos and imagery called “interestingness,” which evaluates videos on general terms. Looking at what’s memorable offers a more specific understanding of what will stay with viewers, since memorability is now understood to be a distinct brain response that can be measured across groups of people. (This notion is backed up by recent research in cognitive science and psychology.)

Using memorability as a metric is also a good way for professional ad-creators to pre-test their creative campaigns before they go live, Shekhar says. The international advertising world seems to be catching on, too: Shekhar’s team’s measurement compared favorably to that used in the Cannes Creative Effectiveness Lions, a competition for ads, where the top few ads were tested for how memorable they were.

The Adobe researchers studying video memorability also participate in competitions to predict the memorability of videos. A 2019 competition, the MediaEval Benchmarking Initiative, uses Shekhar’s group’s paper as one of its reference materials.

Shekhar and team plan to continue to pursue the connection between the videos we enjoy watching and how well we remember them afterwards.